“A cosmic eucharist of waves and particles” – Russell Hoban

I wrote this review of Amaryllis Night and Day by Russell Hoban for the TLS in 2001. At that time, Hoban was still a niche author, writing about uncool stuff in a way that was distinctly unfashionable. Literati got sniffy about the occasional whiffs of sci-fi and fantasy in his work. “Real” novelists wrote slick, sexy realism with a cynical sheen, not shamanistic tangles of myth and environment. I’m glad the wheel has turned since then. Riddley Walker has always been my favourite novel and one that gains in depth and meaning as the years pass.

“Writing this now I have the sudden crazy notion that everybody at birth is issued a little box of images, music, words and a few other things that will appear and reappear in varying combinations all through life.”

So says Peter Diggs, the hero of Russell Hoban’s novel, Amaryllis Night and Day. Diggs could be describing Hoban’s writing habits and the recurring obsessions he has pursued throughout his ten novels, numerous children’s books, poetry and librettos.

Most writers have a core of material, a little box of images and words, which they delve into. Hoban relies upon this matter to an exceptional extent. While his fictional settings range from contemporary London and eleventh century Antioch, to deep space and the post-apocalyptic future, all his pieces address the same philosophical questions and inhabit similar mental territory. At the age of nearly 76 he is experiencing a burst of productivity, publishing three novels in just over three years.

Many readers would struggle to name any of Hoban’s titles, yet most have encountered his work. The best known are the Frances picture stories, the children’s novel The Mouse and His Child (1967), which became an animated film, and his 1975 novel Turtle Diary, which was filmed with a screenplay by Harold Pinter. All these works consider the same existential dilemmas; who are we and what are we here for?

The basics are all there in The Mouse and His Child, one of those sophisticated children’s books that were never intended for kids. A pair of clockwork mice struggle to attain self-winding, enduring a “painful spring, a shattering fall, a scattering regathered.”

Russell Hoban was a driven author: “I describe what I do not understand because I am lived by it. Yes, that’s what it is, why I have no choice, why I am compelled”, says the disembodied narrator of Pilgermann (1983), his most metaphysical novel. Pilgermann is merely “waves and particles” floating through time and space and Hoban acts as Pilgermann’s receiver. Hoban thinks that authors should behave as if they were a unique type of short-wave radio that can tune into and broadcast aspects of the universal. In John Haffenden’s Novelists in Interview (1985), he explains: “All kinds of flashes and flickers, bleeps and glimmers come into the mind, and it is my belief that the artist must deal with all of them.” In an autobiographical essay published in his collection of prose pieces, The Moment Under The Moment (1992), Hoban maintains “the universe is continually communicating itself to us in a cosmic eucharist of waves and particles.”

This approach is not as wet as it sounds. His belief that we are all made from the dust of stars is supported by quantum physics, particularly the theories of David Bohm, who posited that the universe is a single connected matrix of matter and space. Bohm was convinced that all of the universe, even its tiniest subatomic particles, can receive information about the rest. He explained this concept using the analogy of an aeroplane obtaining data via radio signals.

Weird science is useful to Hoban because it offers justification for reality shifts and twilight zones. His most obvious references to quantum theory occur in his science fiction fantasy, Fremder (1996), a truly Hobanesque production featuring a disembodied mind, lots of flickering between states of being via teleportation, loss, desire, and many words in CAPITAL LETTERS.

Hoban’s work flirts postmodernly with a number of genres including magic realism, fantasy and historical fiction, but resists categorisation. This is one of the factors that make it so exciting and provoking. Amaryllis Night and Day is in part a ghost story with a solidly-detailed contemporary London supplying the backdrop for Hoban’s fancy sleights of hand. Diggs and his new love Amaryllis enter each other’s dreams and find that they are haunted by the same woman. Typically, Hoban is less interested in the supernatural than the process of translation between reality and imagination, leading to digressions about the complexities of Mobius strips and Klein bottles, contradictory structures which seem to pass through themselves. Older ways of knowing are featured in one rather New Agey chapter where Diggs and his previous, witchy girlfriend tread a turf maze, an ancient pattern designed as a map for the soul’s flight.

The Klein bottles are the give-away. Behind Hoban’s interest in the peculiar lies a straightforwardly old-fashioned notion of the writer as a vessel to be filled with divine inspiration.

Divination is an unpopular method in the clean, bright era of the New Puritans. To many younger authors producing slick, sexy books about London elites it whiffs of bedraggled 1950s’ and 60s’ ideas about myth and shamanism, the hippie approach Philip Larkin mocked as raiding the myth kitty. This attitude dismissed Ted Hughes as a dotty has-been, until that sudden, astonishing series of publications during the last two years of his life forced his critics to recant. Writing older authors off because their ideas seem outdated is always a dangerous business.

Hoban shares with Hughes a similar notion of the function of the artist as shaman and mouthpiece of the tribe, whose purpose is to tune into what’s really going on. This is a serious intellectual task and Hoban has criticised the contemporary novel for failing the public by being “simply the conveying of chunks of experience wrapped up in some kind of story.”

Riddley Walker

When Hoban’s methods work, the result is spectacular. In 1980 he published Riddley Walker, one of the defining novels of the 1980s. Like the other contenders, Midnight’s Children by Salman Rushdie (1981), Money by Martin Amis and 1982 Janine by Alasdair Gray, (both 1984), Riddley Walker is told in the first person by a voice so powerful that it levitates off the page and invades the reader. Hoban has described the process of writing the book in appropriately spooky terms: “Something got hold of me and didn’t let go until it got itself down on paper in the way that it wanted to be.”

Set in Kent thousands of years after nuclear war has destroyed civilisation, Riddley Walker is enchantingly political, another characteristic shared with its contemporaries. However, the book is primarily concerned with the journey of the self from ignorance to knowledge. As with Money, the novel’s greatest strength is its linguistic adventurousness. Hoban writes in a broken-down phonetic argot, one that, incidentally, exploits the colloquism “innit” before Amis co-opted it for his London lowlifes.

Writing this way enables Hoban to explore the flexibility of language and its double meanings. When Riddley’s father dies, the hero says “I wer the loan of my name.” Playfulness and multiplicity of interpretation are essential features of Hoban’s style, which is stacked with puns and deliberate mishearings intended to dislocate reality. In Kleinzeit (1974) the hero is pursued by the phrase “barrow full of rocks”, which in the minds and mouths of other characters morphs into “harrow full of crocks” and “morrows cruel mock”. Later the phrase is revealed as an unlikely mnemonic for a line from Milton’s L’Allegro (1632). It is as if Hoban wants to grab words and beat accretions of meaning off them like dirt from a rug to reveal a hidden and quite different pattern.

Words are equally allusive and unreliable in Amaryllis Night and Day. Diggs and Amaryllis dread travelling on a nightmare bus bearing the mysterious destination “Finsey Obay”. The actual words “Finsey Obay” remain an empty signifier, and when the destination is finally revealed as Beachy Head it has immense resonance but proves almost as unrelated lexically as “barrow full of rocks” is to “Untwisting all the chains that ty / The hidden soul of harmony.”

The terrifying bus is part of Hoban’s wider attempt to find names and handles for ungraspable concepts. In Amaryllis Night and Day he tinkers with the word “balsam” until it becomes a symbolic key to a set of memories and experiences. Elsewhere, he frequently uses synesthesia, describing one sense in terms of another. Thus the hero of Angelica’s Grotto (1999) “tastes” the wine gum colours of traffic lights after he becomes embroiled in the unreal world of internet porn. In the short story Call Girl (1995) the device is utilised as a plot twist enabling an opera singer whose voice “makes pictures” to murder her unfaithful boyfriend. Such contrivances are employed in the hope of leading the reader into a paradoxical space where indescribable experiences can be conveyed.

Reading Hoban it can be difficult not to fight with prose that so obviously has designs on you. Perhaps this is why he continues to write for children as well, since children are more receptive to the fantastical and less insistent that stories should obey certain rules. Opera and poetry too offer the chance to plunge immediately into abstract ideas without the nuisance of characterisation or A to B plotlines.

For adults, much of the pleasure of reading Hoban’s later novels is to be found in unravelling the labyrinth as prompted, responding to layers of meaning gathered from previous works. Elements such as the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, Hermes, the London Underground, yellow A4 paper, Vermeer and November evenings don’t need to be explained to the initiated, mentioning them is enough to signify a whole philosophy. Single words become hermetic talismans; “tawny” is the most persistent of these, appearing at least once in most of Hoban’s novels and always sited in passages of marked stylistic extravagance and shimmer.

The recycling of words and ideas from book to book chimes with Hoban’s proclaimed interest in language as archaeology, “full of the remnants of dead and living pasts”, that he pursued so effectively in Riddley Walker. It offers the clue to his writing as a whole, which is the notion of survival and wholeness. Things in his novels are always coming apart, losing bits of themselves and having their most enduring elements put back together again. It’s no coincidence that two of the most lasting things imaginable, stones and myths, feature prominently and continually. As Diggs says: “When I find a theme I can do something with I tend to stay with it for a while.”

Hoban’s personal circumstances have a bearing on this. He was born in Landsdale, Pennsylvania, the son of Russian Jews from Ukraine. In 1969 his fascination with English ghost stories prompted a move to London, where lived for the rest of his life. Being Jewish gives the concept of survival clear implications, ones that are considered further in Pilgermann and Mr Rinyo-Clacton’s Offer (1998). Being American is equally significant. In an essay on the American Dream, Hoban talks about the spirit of America being a journeying one. “Everyone in America has always been on the way from one place to another, one condition to another.” He illustrates his meaning by referring to an Edward Hopper painting of a gas station that shows a long road travelling away into the distance. The road’s emptiness and possibilities represent a distinctly American version of the negative capacity within every artist. This same painting reappears in Amaryllis Night and Day when Amaryllis asks Peter to dream it for her. They both succeed in entering the picture and travelling off down the highway. “There are many talented people who never will become painters, writers, or composers; the talent is in them but not the empty spaces where art happens”, says Diggs, an artist.

In his recent memoir, Experience, Martin Amis implies that it is counter productive for writers to see and understand the private myths that animate their work. Furthermore, such revelations are impossible without malign external interference. “I have seen what perhaps no writer should ever see: the place in the unconscious where my novels come from. I couldn’t have stumbled on it unassisted,” he writes. Russell Hoban has spent nearly forty years seeking to divine exactly what that unconscious place contains. His books tell the story of those inquiries.

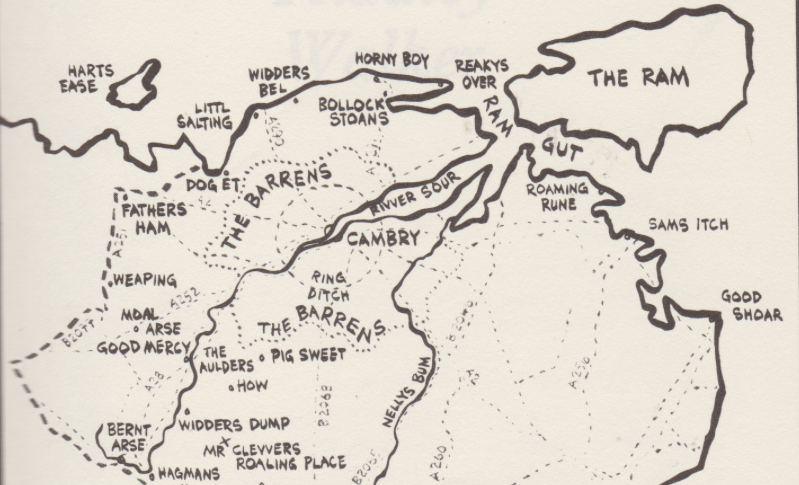

Image shows a detail from the map in Riddley Walker.