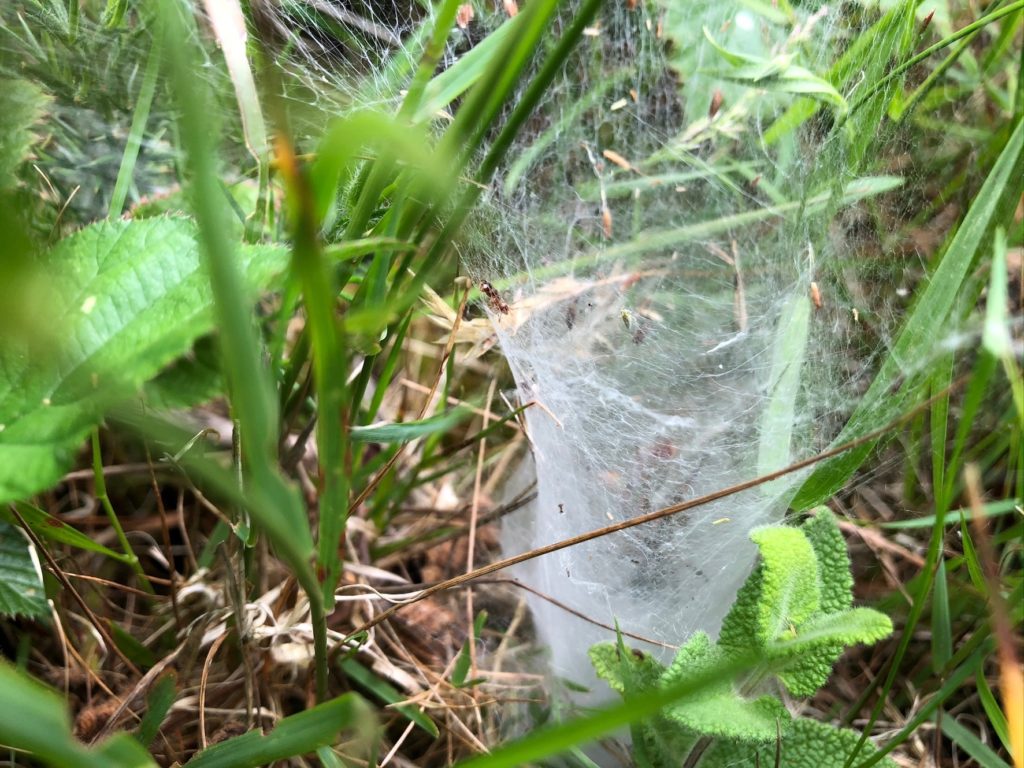

Labyrinth spider lairs shine with dew

On dew-laden early mornings, funnel-shaped webs shine in the long grass like crystal vases. Complicated gantries hang between plant stems, tapering down to tubular tunnels, so densely spun that the tough silk appears white.

Despite their appearance, these are not the lairs of some poisonous funnel-web spider, but the homes of the labyrinth spider (Agelena labyrinthica), a species common in rough, uncut grasslands of southern England. They get their name from the complicated hidden passages and chambers within their tunnels.

Harmless to humans, labyrinth spiders feed on grasshoppers and crickets. Catching such athletic, bulky insects requires a sturdy trap that can’t be kicked apart too easily.

Paintings on cobwebs

Agelenidae cobwebs are so strong and thickly woven that in the 16th century, monks in the Austrian Alps began layering them together to create tiny canvases for religious miniatures. Great care was needed in picking out all the droppings and fragments of prey before they could be painted on.

It’s difficult to get a clear view of these shy, nervy spiders. They wait within the shrouded entrance to their nests, legs hunched up, abdomens raised, rounded pedipalps outstretched like bristly boxing gloves. When I kneel down and poke a web with a grass stalk, the spider instantly disappears, alarmed by such a crude disturbance.

Its legs are equipped with clusters of sensitive hairs that can pick up the smallest airborne currents, even electrical charges. But by blowing very softly, I create a gentle vibration that tempts it out into view.

Covered in downy hairs, its body has the pale, sugary sheen of a boiled sweet, humbug-striped in dingy yellow and brown. Its abdomen is marked with a double row of light chevrons ending in two elongated spinnerets. These are large spiders, especially the females, whose bodies can be nearly 2cm long. Males tend to be much smaller.

Over the next few weeks, the males will approach the females by cautiously tapping the edges of their webs. If a female is ready, she will invite the male in to mate. Mating can take several hours, during which the female lies, motionless, on her side in an almost catatonic state. As long as other food is plentiful, the male will probably survive the encounter.

This piece was first published in the Guardian Country Diary on 10 July 2020.