Resisting rottenness – Greta Thunberg and family

Waiting for Greta Thunberg to speak in Bristol earlier this year, the cameras kept focusing on an eye-catching knitted doll, borne aloft in the crowd on a bamboo cane. It was a simple rendition of Greta iconography: yellow coat, brown wool plaits, angry eyes, a sign saying “Skolstrejk för Klimatet”.

Who is Greta Thurnberg? The person who finally appeared on the podium at College Green looked much younger than seventeen. She was shorter and slighter than the other youth climate strikers, and the microphone stand towered over her head.

Greta’s combination of anorak, woolly hat, schoolgirl hair and unmade-up face is not a style generally favoured by British teenagers. But her body language is even more different than her clothes. Although she appears shy, she lacks the genuflections towards power expected of young women in Western culture. It may be this silent absence of submission that older people, men and women but especially men, find so challenging.

Watching the Bristol event live on BBC West’s Facebook page, I could see a simultaneous stream of angry comments from older viewers, most of them men. They were cross because Thunberg had a mobile phone, wore clothes she hadn’t hand-made herself, travelled to Bristol by diesel train – diesel, that is, rather than electric – and used domestic electricity. All these were cited as free choices and therefore marks of deep environmental hypocrisy.

According to these commentators, Thunberg’s greatest crime was being young. They were enraged by the idea that younger generations might look to her for leadership, rather than listening to older people. Teenagers in general were too selfish, too focused on their gadgets, too indulged: “WHAT A HYPOCRITE”, wrote one man. “It’s hilarious, all these school kids preaching to us oldies that we ruined the planet! Back in the 60s and 70s and 80s not a plastic bottle to be seen it was all glass that were reused, pop bottles taken back to the shop … I think these youngsters need to take a look in a recycled mirror and think was it my wasteful generation who are ruining the planet.”

Folk tales of a thrifty past

Versions of this folk tale about our supposedly thrifty past generally appear in every comment thread about the environment. It’s not just social media; the myth is a staple of grassroots print outlets, cropping up frequently in parish magazines, those trusty almanacs of older, predominantly white, conservative thought. These accounts generally shift aspects of life arguably experienced in the 1940s to a more recent period. It’s typical that the Bristol man claimed plastic bottles weren’t used in the 1970s and 80s. Others remember differently: when the novelist and children’s writer Russell Hoban visited Paxos in September 1978, he found it littered with plastic rubbish. “Beautiful Ionian island in the sparkling blue sea and it’s got plastic mineral-water bottles all over it”, he recalled in an essay from 1983, “Pan Lives”. “Why do perfectly good children become such rotten grown-ups?” he asked.

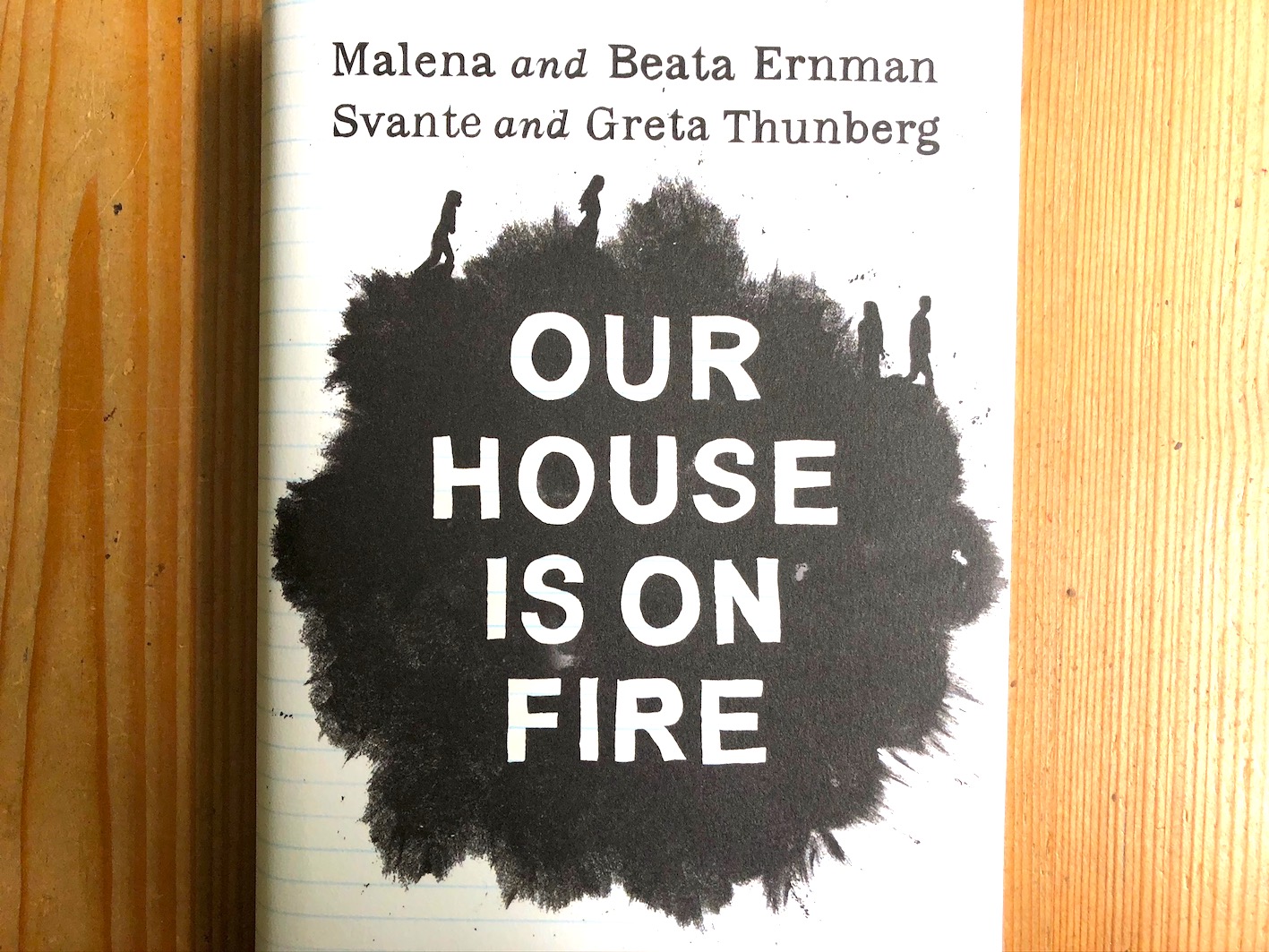

Our House Is on Fire is a story of resistance against rottenness. It’s largely told by Malena Ernman with contributions from her husband Svante Thunberg, and is about their two daughters, Greta and Beata, who are also credited as co-authors. It tells how at the age of eleven, Greta stopped eating and speaking, unable to cope with the dissonance she perceived in the world around her. Ernman writes: “What happened to our daughter can’t be explained simply by a medical acronym or dismissed as ‘otherness’. In the end she simply could not reconcile the contradictions of modern life”.