The Hornet Oak

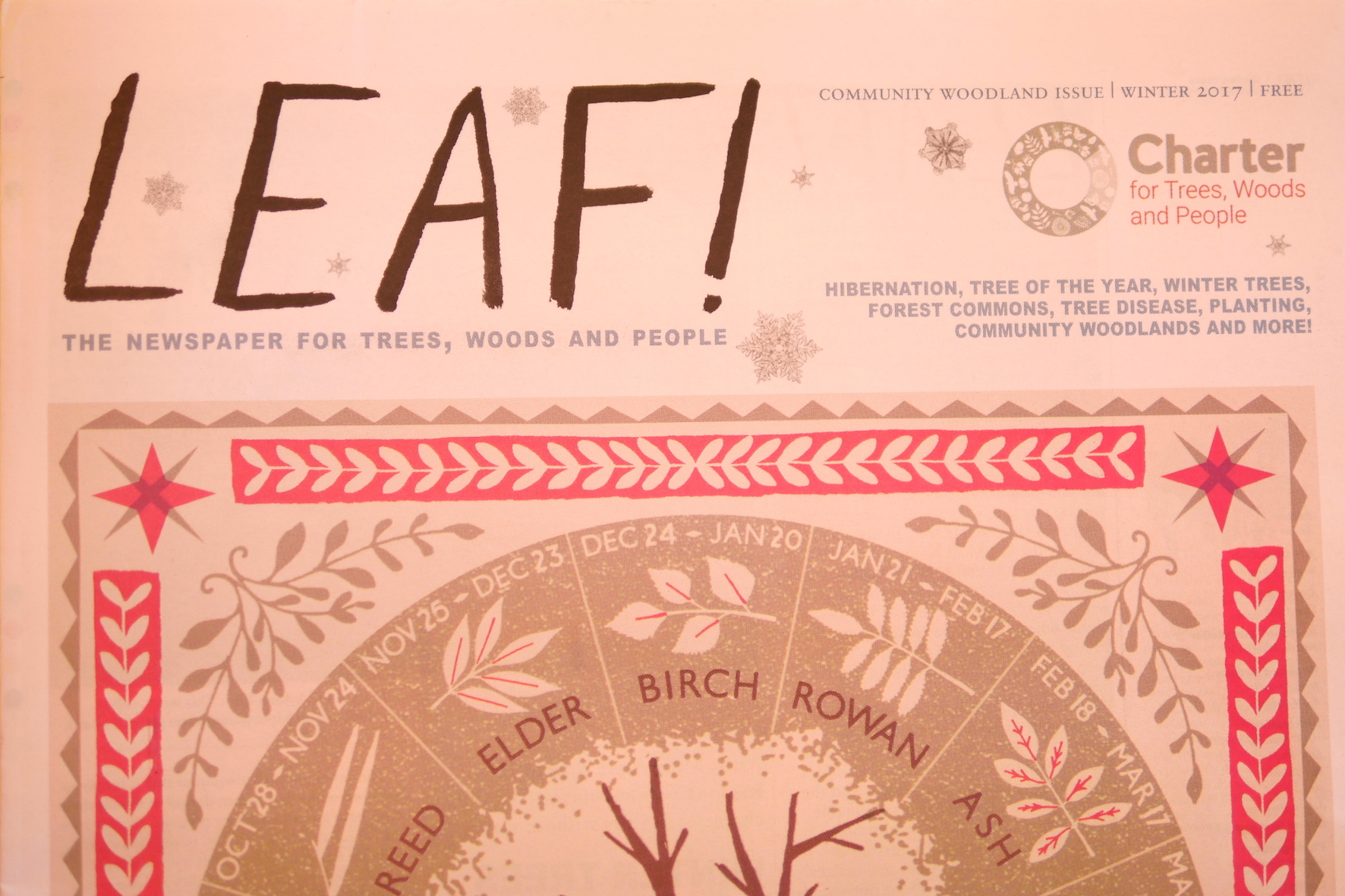

The tale of the Hornet Oak in the coppice near where I live. This piece was originally written for the Winter 2017 edition of LEAF!, a seasonal newspaper produced jointly by the environmental charity Common Ground and The Woodland Trust.

Deep in the coppice behind our house is an old, hollow oak that shelters a kingdom of creatures. It’s a ‘stag oak’, which is a venerable oak with a couple of dead, bare branches that rise like kingly antlers. I call it the Hornet Oak though because one summer a colony of European hornets nested inside, zipping in and out hunting insects and gathering honeydew sap. In spring when the first foliage flushes gold, woodpeckers drum the trunk for grubs. In autumn when the leaves turn bronze, it scatters acorns for the jays.

In winter, life retreats inside. Poke your head into the narrow opening between crumbly, wormy bark and you sense a still, cold space. It smells of loam and leaf mould. Shine a torch around and the light catches a silver pattern of snail trails, thick swags of spiders’ web and the bitten evidence of a myriad scuttling, creeping, crawling things.

It’s an ideal place for bats to hibernate. During hibernation, bats need roosts that are cool and stay at a steady temperature. Small tree holes or even cracks under thick bark are ideal as they are well insulated, dark and dry. Oak, ash and beech trees are particularly suitable but any large tree with cavities and splits is a potential bat roost.

I don’t know for sure whether bats hibernate in the Hornet Oak – it would disturb then too much to find out. But I have walked there in summer with a bat detector and heard the calls of three different species – long-eared, soprano pipistrelle and whiskered – and seen them flitting through the dusk. I know they could be hibernating somewhere in those woods, tucked away in their secret crevices, cracks and holes, sleeping like the trees and waiting for spring.