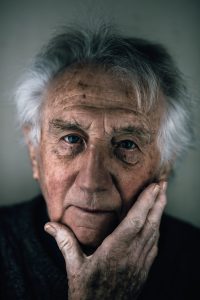

Brian Rice – 60s artist regenerated by the countryside

Evolution of an artist: A piece about Brian Rice, which appears in the Early Autumn 2016 edition of Manor South West.

LONDON in the 1960s was especially cool for those in the art world. The crowd around the Royal College of Art included David Hockney, Derek Boshier, Peter Blake, Joe Tilson and Allen Jones. Part of this group, one of the coolest of the cool, was painter and printmaker Brian Rice.

Rice mingled with fashion designers, rock musicians and models. Film director Michelangelo Antonioni interviewed him when researching the background for Blow Up, which was originally going to be about a painter rather than a photographer. Rice dated the fashion designers Marion Foale and Sally Tuffin and was friends with rock musicians, particularly Ian Stewart, the keyboard player and co-founder of the Rolling Stones.

The work Rice produced is iconic of the time. Abstract blocks of colour in bold patterns and modular paintings made from smaller individual canvases assembled to make a bigger painting. Today they look absolutely of their time, as redolent of the Sixties zeitgeist as a Habitat ‘continental quilt’ cover. Yet it was partly serendipity that Rice made these modular works. In 1963 he was living in a basement flat in Cromwell Road with two tiny rooms and a larger living space. His studio was one of the small rooms, only about eight feet square. There wasn’t room for big paintings.

‘I suddenly thought if I work on small canvases in the studio then take them out and assemble them, it’s an obvious way round this lack of space,’ Rice remembers.

‘Sometimes in the process of assembling them I’d change my mind. They weren’t a fait accomplit.’ Metropol (1965) was originally going to be a rectangle, but ended up stepped like a monument.

Rice’s paintings and prints appeared in many TV commercials, fashion shoots and set designs. They were used to advertise products including a new range of whitewood furniture, Hoover gas fires and British wool carpets. They indicated modern, they indicated cool. They were hired to dress film sets. His images feature in Karel Reisz’s film Morgan: A Suitable Case for Treatment (1966), in Robert Freeman’s The Touchables (1968) and Michael Ritchie’s The Candidate (1972). They were used in an ad campaign for White Horse Whisky, appeared at the Ideal Home exhibition and featured in House & Garden. Rice also designed his own rugs and executed a striped pillar for Pauline Fordham’s fashion boutique Palisades on Ganton Street.

The modular pictures were one of several stages Rice’s work went through during the decade. In the early years, he had a brief political period, producing two ‘protest’ paintings, Megaton, an anti-nuclear statement, and Persil for Whites Only, an anti-apartheid one. Although these were the nearest to Pop Art that Rice produced, he was never a Pop Artist. The influence of the American Abstract Impressionists was much stronger and he had two shows at Dennis Bowen’s New Vision Centre Gallery, which had a more Continental and avant-garde focus. Rice was always more European than American in his leanings.

This Europeanism was reflected in his admiration of the Bauhaus. Rice attended a seminal Bauhaus exhibition at the Royal Academy, which stimulated his interest in colour theory. In particular, he became intrigued by Goethe’s colour theory and the supposed ideal proportions for primary colours: three parts yellow, six parts red, eight parts blue. By the early Seventies, this obsession would produce a series of triangular paintings and prints, each made up of smaller triangles of carefully graded colour mixtures of red, yellow and blue.

Colour theory went hand-in-hand with his passion for Art Deco, a theme which began to feed into Rice’s paintings from the mid 60s. Deco Sunrise (1966) is an early and vibrant gouache example, in which the sun’s rays burst from the bottom left-hand corner and radiate outward, filling the picture space. Rice began noting examples of the Deco sunrise pattern being used in everyday life and in 1972 he produced a book, The English Sunrise, co-authored with photographer Tony Evans. The book had practically no text and was simply a collection of found sunrise motifs – on doors, badges and gates, a cigarette case and powder compact, fanlights, windows and an ice cream wafer. It won three awards.

By the end of the Sixties Rice was an established abstract artist. Why was his work forgotten for twenty years? What happened to him?

Colour theory and his triangle works literally painted Rice into a corner. He lost faith in his career. The final crisis came in 1975 when he exhibited his triangular paintings at Brighton Polytechnic Gallery: ‘I remember sitting in the exhibition and thinking “this is really boring, and I don’t want to spend the rest of my life doing this. I want to find something which is more unique to me.”

Although Rice stopped painting for a while, his regeneration had already begun. In 1971 he’d bought a cottage in Lyme Regis in Dorset and was spending time there while still living in London. His mother’s family was from Lyme and Rice had grown up in Montacute in Somerset. He was a West Country boy by birth and this return to his roots was reassuring. He was further cheered by finding two metal-framed chairs designed by Chermayeff (one of his admired artist/designers) on the local rubbish tip.

In 1978 he moved out of London permanently and bought a remote, 50-acre sheep farm on the flanks of Eggardon Hill near Bridport. He brought in extra money by teaching part-time at Brighton College of Art (now University of Brighton), but most of his time was taken up with working the land and restoring the 17th-century farmhouse. In the process he discovered Bronze Age ceramic fragments and an 18th-century Donyatt pottery dish painted with the face of a Green Man, a symbol of rebirth. His archaeological finds inspired a new artistic direction, focused on the landscape and ancient traces of habitation, and he started to paint again.

Rice’s life and art merged more closely in the early 1980s when a relationship break-up forced the sale of the farm and he bought a dilapidated 15th-century house near Hewood on the Dorset/Devon/Somerset borders. Newhouse was a different proposition to the sheep farm. Equally remote, it was in a terrible state of repair. For the first couple of years, Rice effectively camped in its shell while single-handedly rebuilding parts of it around him.

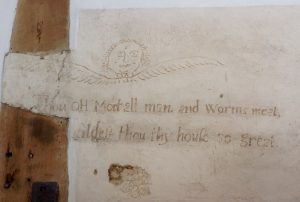

It took Rice the next 30 years to fully restore Newhouse. During this time he uncovered fascinating traces of its past, including inscriptions and items of folk magic. Most astounding was a 17th-century inscription on a bedroom wall, now used as his studio, which reads: ‘Thou oh Mortall man, and worms meat, [why] buildest thou thy house so great’.

Newhouse had six acres of pasture and he kept a few ewes and bred Suffolk rams. This continuing commitment to the land nurtured his artistic resurgence, producing mature artworks imbued with a sense of place and deep connection to nature.

‘It’s important to me that my art reflects the environment where I live,’ Rice says. ‘Digging the garden you find the objects that have been lost or abandoned by your predecessors.’

All this literal digging into the past revealed common patterns that people use time and time again across cultures and centuries.

‘I think there are certain shapes that are in your psyche and you find them in different sources and at different times, but the actual shapes remain very consistent.’

These shapes and patterns became the subject of his work. In 1995 he held his first exhibition for 20 years. The solo show at The Meeting House in Ilminster was followed in 1998 by his ‘Art and Archaeology’ solo exhibition at Somerset County Museum in Taunton, where he displayed his works alongside his numerous finds from the Newhouse restoration, including around 3,000 shards of pottery. Over the next decade, exhibitions in London, St Ives and Dorset followed, including two shows in Cork Street, London: a retrospective at Messum’s in 2001, and a highly successful show of his 1960s work at the Redfern Gallery in 2014.

In 2013, Rice published a catalogue raisonné of prints, and he has just published a full catalogue of all his paintings. Brian Rice: Paintings 1952-2016 features an introductory essay by leading art critic Andrew Lambirth, which gives a full biographical and critical background. It was published to coincide with Rice’s 80th birthday.

With two such landmark publications having been issued, it would be tempting to think that Rice is signalling a late retirement. Not so – since the paintings book went to print in June, he continues to make new paintings. He’s been so busy that he hasn’t had time to produce any prints, but he says he might return to printmaking next year. There are also his long-running small 3D and found object works, which have not been catalogued at all so far.

‘At some point I hope there will be another book of late works, combining all the things I’ve done,’ he promises.

Meanwhile, you can see Rice’s work at two landmark exhibitions coming up over the next year in Dorset and St Ives. The Art Stable Gallery in Child Okeford is showing a selection of his work from throughout his career from 17 September to 22 October. The Belgrave Gallery in St Ives is staging an exhibition in spring 2017, exact dates to be confirmed.

Brian Rice: Paintings 1952-2016 is published by Sansom & Company with an introductory essay by Andrew Lambirth. To order a signed copy email jacy.wall@btinternet.com Price is £45, P&P included.